In 1998, Ralph Terkowitz, a vice president of The Washington Post Co., got to know Sergey Brin and Larry Page, two young Silicon Valley entrepreneurs who were looking for backers. Terkowitz remembers paying a visit to the garage where they were working and keeping his car and driver waiting outside while he had a meeting with them about the idea that eventually became Google. An early investment in Google might have transformed the Post's financial condition, which became dire a dozen years later, by which time Google was a multi-billion dollar company. But nothing happened. “We kicked it around,” Terkowitz recalled, but the then-fat Post Co. had other irons in other fires.

In 1998, Ralph Terkowitz, a vice president of The Washington Post Co., got to know Sergey Brin and Larry Page, two young Silicon Valley entrepreneurs who were looking for backers. Terkowitz remembers paying a visit to the garage where they were working and keeping his car and driver waiting outside while he had a meeting with them about the idea that eventually became Google. An early investment in Google might have transformed the Post's financial condition, which became dire a dozen years later, by which time Google was a multi-billion dollar company. But nothing happened. “We kicked it around,” Terkowitz recalled, but the then-fat Post Co. had other irons in other fires.

Such missteps are not surprising. People living through a time of revolutionary change usually fail to grasp what is going on around them. The American news business would get a C minus or worse from any fair-minded professor evaluating its performance in the first phase of the Digital Age. Big, slow-moving organizations steeped in their traditional ways of doing business could not accurately foresee the next stages of a technological whirlwind.

Obviously, new technologies are radically altering the ways in which we learn, teach, communicate, and are entertained. It is impossible to know today where these upheavals may lead, but where they take us matters profoundly. How the digital revolution plays out over time will be particularly important for journalism, and therefore to the United States, because journalism is the craft that provides the lifeblood of a free, democratic society.

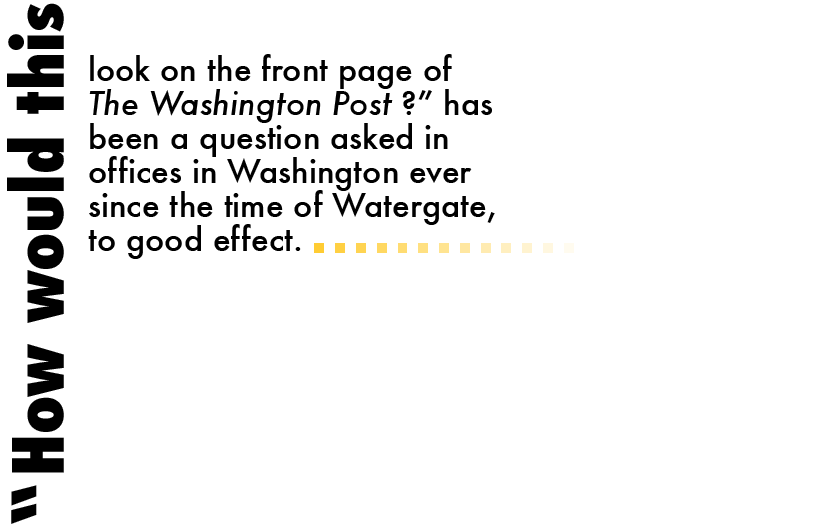

The Founding Fathers knew this. They believed that their experiment in self-governance would require active participation by an informed public, which could only be possible if people had unfettered access to information. James Madison, author of the First Amendment guaranteeing freedom of speech and of the press, summarized the proposition succinctly: “The advancement and diffusion of knowledge is the only guardian of true liberty.” Thomas Jefferson explained to his French friend, the Marquis de Lafayette, "The only security of all is in a free press. The force of public opinion cannot be resisted when permitted freely to be expressed.” American journalists cherish another of Jefferson's remarks: “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

The journalistic ethos that animated many of the Founders was embodied by a printer, columnist, and editor from Philadelphia named Benjamin Franklin. The printing press, which afforded Franklin his livelihood, remained the engine of American democracy for more than two centuries. But then, in the second half of the 20th century, new technologies began to undermine long-established means of sharing information. First television and then the computer and the Internet transformed the way people got their news. Nonetheless, even at the end of the century, the business of providing news and analysis was still a profitable enough undertaking that it could support large organizations of professional reporters and editors in print and broadcast media.

Now, however, in the first years of the 21st century, accelerating technological transformation has undermined the business models that kept American news media afloat, raising the possibility that the great institutions on which we have depended for news of the world around us may not survive.

Pulse news aggregator app.

source: alphonsolabs.com

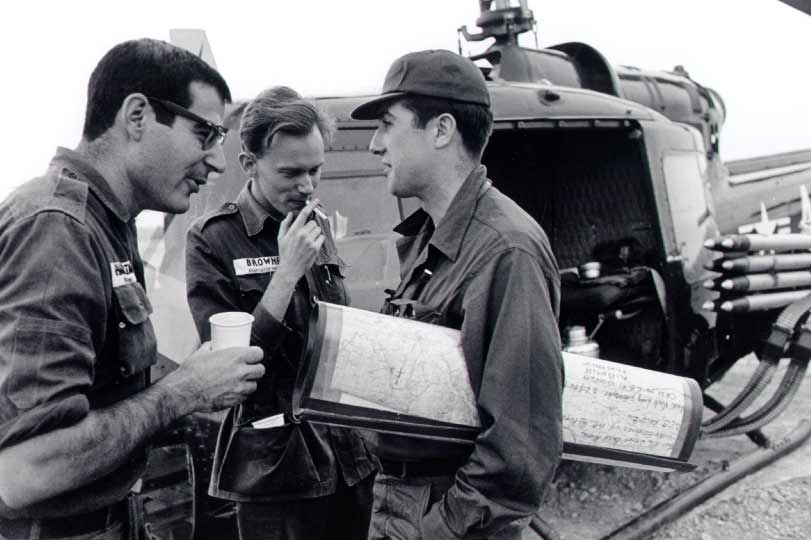

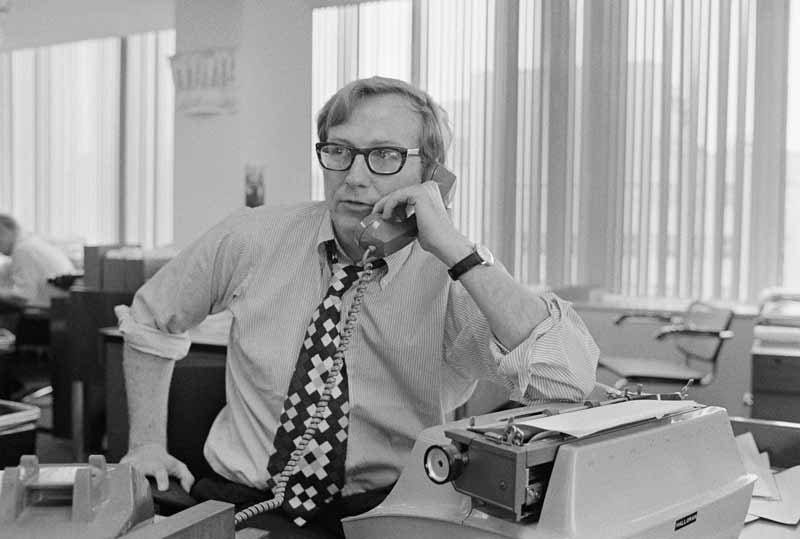

These are painful words to write for someone who spent 50 years as a reporter and editor at The Washington Post. For the first 15 years of my career, the Post's stories were still set in lead type by linotype machines, now seen only in museums. We first began writing on computers in the late 1970s, which seemed like an unequivocally good thing until the rise of the Internet in the 1990s. Then, gradually, the ground began to shift beneath us. By the time I retired earlier this year, the Graham family had sold the Post to Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, for $250 million, a small fraction of its worth just a few years before. Donald Graham, the chief executive at the time, admitted that he did not know how to save the newspaper.

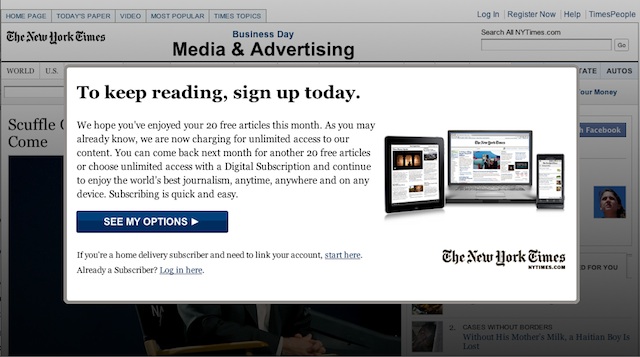

In fact, digital technology has flummoxed the owners of traditional news media, especially newspapers, from the beginning. For example, in 1983, in the early years of computerized production of newspapers when almost no one knew what was coming, The New York Times almost committed digital suicide. The Times decided it only needed to retain the rights to the electronic versions of its stories for 24 hours after publication. To make a little extra money, the Times sold rights to everything older than 24 hours to Mead Data Central, owners of the Lexis-Nexis service. Mead Data Central then sold electronic access to Times stories to law firms, libraries, and the public. By the early 1990s, as the Internet was becoming functional and popular, this arrangement was a big and growing problem: newspapers, including the Times, were planning “online,” computerized editions, but the Times had sold control of its own product to Mead Data.

Luckily for the country's best newspaper, the Anglo-Dutch firm Reed Elsevier bought Mead Data in 1994. The sale triggered a provision in the original Times-Mead contract that allowed the Times to reclaim the electronic rights to its own stories. That enabled the Times to put its journalism online in 1995.

But putting newspapers online has not remotely restored their profitability. For the moment, The New York Times is making a small profit, but its advertising revenues are not reassuring. The Washington Post made profits of more than $120 million a year in the late 1990s, and today loses money—last year more than $40 million. Newsweek magazine failed, and Time magazine is teetering. Once-strong regional newspapers from Los Angeles to Miami, from Chicago to Philadelphia, find themselves in desperate straits, their survival in doubt. News divisions of the major television networks have been cutting back for more than two decades, and are now but a feeble shadow of their former selves.

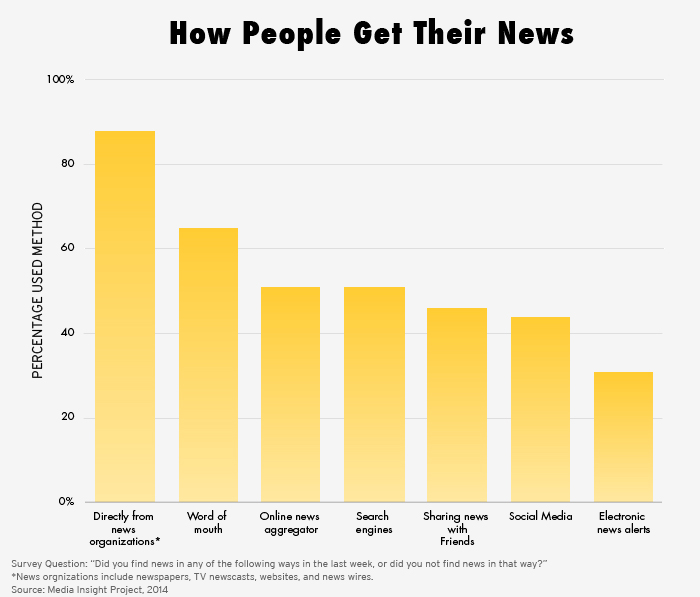

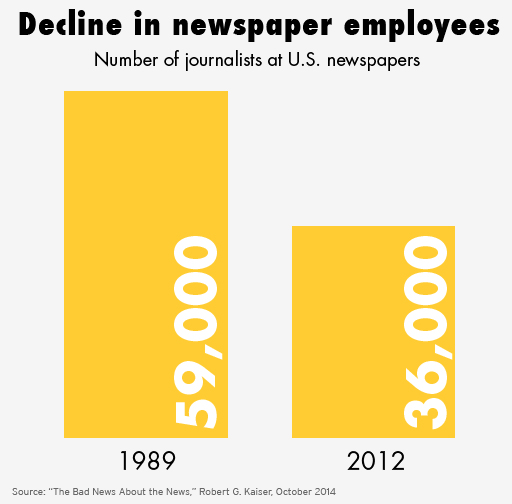

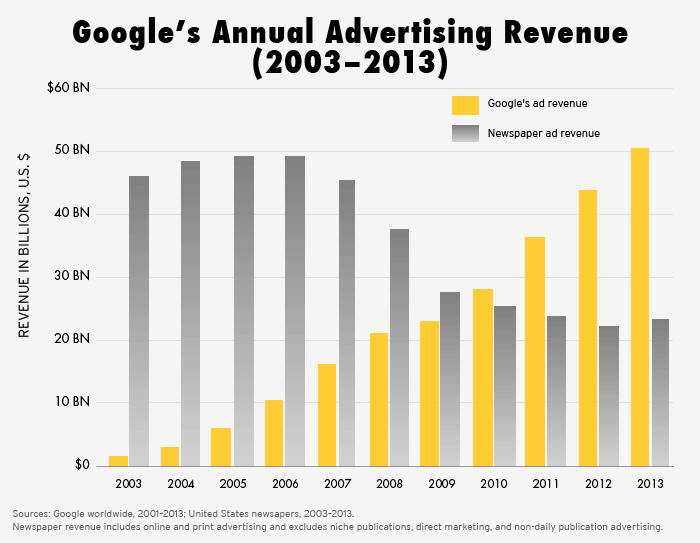

Overall the economic devastation would be difficult to exaggerate. One statistic conveys its dimensions: the advertising revenue of all America's newspapers fell from $63.5 billion in 2000 to about $23 billion in 2013, and is still falling. Traditional news organizations' financial well-being depended on the willingness of advertisers to pay to reach the mass audiences they attracted. Advertisers were happy to pay because no other advertising medium was as effective. But in the digital era, which has made it relatively simple to target advertising in very specific ways, a big metropolitan or national newspaper has much less appeal. Internet companies like Google and Facebook are able to sort audiences by the most specific criteria, and thus to offer advertisers the possibility of spending their money only on ads they know will reach only people interested in what they are selling. So Google, the master of targeted advertising, can provide a retailer selling sheets and towels an audience existing exclusively of people who have gone online in the last month to shop for sheets and towels. This explains why even as newspaper revenues have plummeted, the ad revenue of Google has leapt upward year after year—from $70 million in 2001 to an astonishing $50.6 billion in 2013. That is more than two times the combined advertising revenue of every newspaper in America last year.

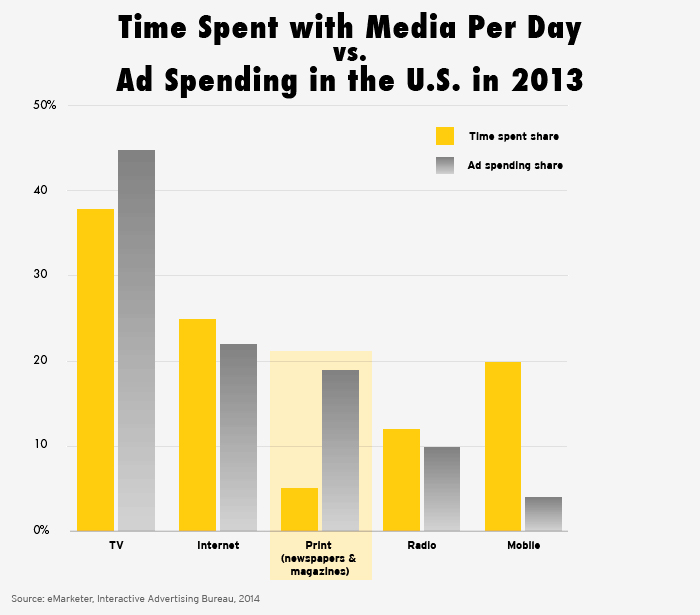

And the situation for proprietors of newspapers and magazines is likely to get worse. One alarming set of statistics: Americans spend about 5 percent of the time they devote to media of all kinds to magazines and newspapers. But nearly 20 percent of advertising dollars still go to print media. So print media today are getting billions more than they probably deserve from advertisers who, governed by the inertia so common in human affairs, continue to buy space in publications that are steadily losing audience, especially among the young. When those advertisers wake up, revenues will plummet still further.

Newspaper Closings

King County Journal

-January 2007Union City Register Tribune

-November 2007Kentucky Post

-December 2007Cincinnati Post

-December 2007Halifax Daily News

-February 2008Albuquerque Tribune

-February 2008San Juan Star

-August 2008Tucson Citizen

-May 16, 2009Rocky Mountain News

-February 2009Baltimore Examiner

-February 2009View sources

News organizations have tried to adapt to the new realities. As the Internet became more popular and more important in the first decade of the 21st century, newspaper proprietors dreamed of paying for their newsrooms by mimicking their traditional business model in the online world. Their hope was to create mass followings for their websites that would appeal to advertisers the way their ink-on-paper versions once did. But that’s not what happened.

The news organizations with the most popular websites did attract lots of eyeballs, but general advertising on their sites did not produce compelling results for advertisers, so they did not buy as much of it as the papers had hoped. And the price they paid for it steadily declined, because as the Internet grew, the number of sites offering advertising opportunities assured that “supply” outstripped “demand.” Advertising revenues for the major news sites never amounted to even a significant fraction of the revenues generated by printed newspapers in the golden age. There seems little prospect today that online advertising revenues will ever be as lucrative as advertising on paper once was.

The other online innovation that has devastated newspapers is Craigslist, the free provider of what the newspapers call “classified advertising,” the small items in small print used by individuals and businesses for generations to buy and sell real estate and merchandise, and to hire workers. Twenty years ago classifieds provided more than a third of the revenue of The Washington Post. Craigslist has destroyed that business for the Post and every major paper in the country.